Organizing mathematical theories in Coq: an overview

- Typeclasses

- Hierarchy Builder

- Packed classes & canonical structures

- Telescopes

- Records

- Modules

- Final thoughts

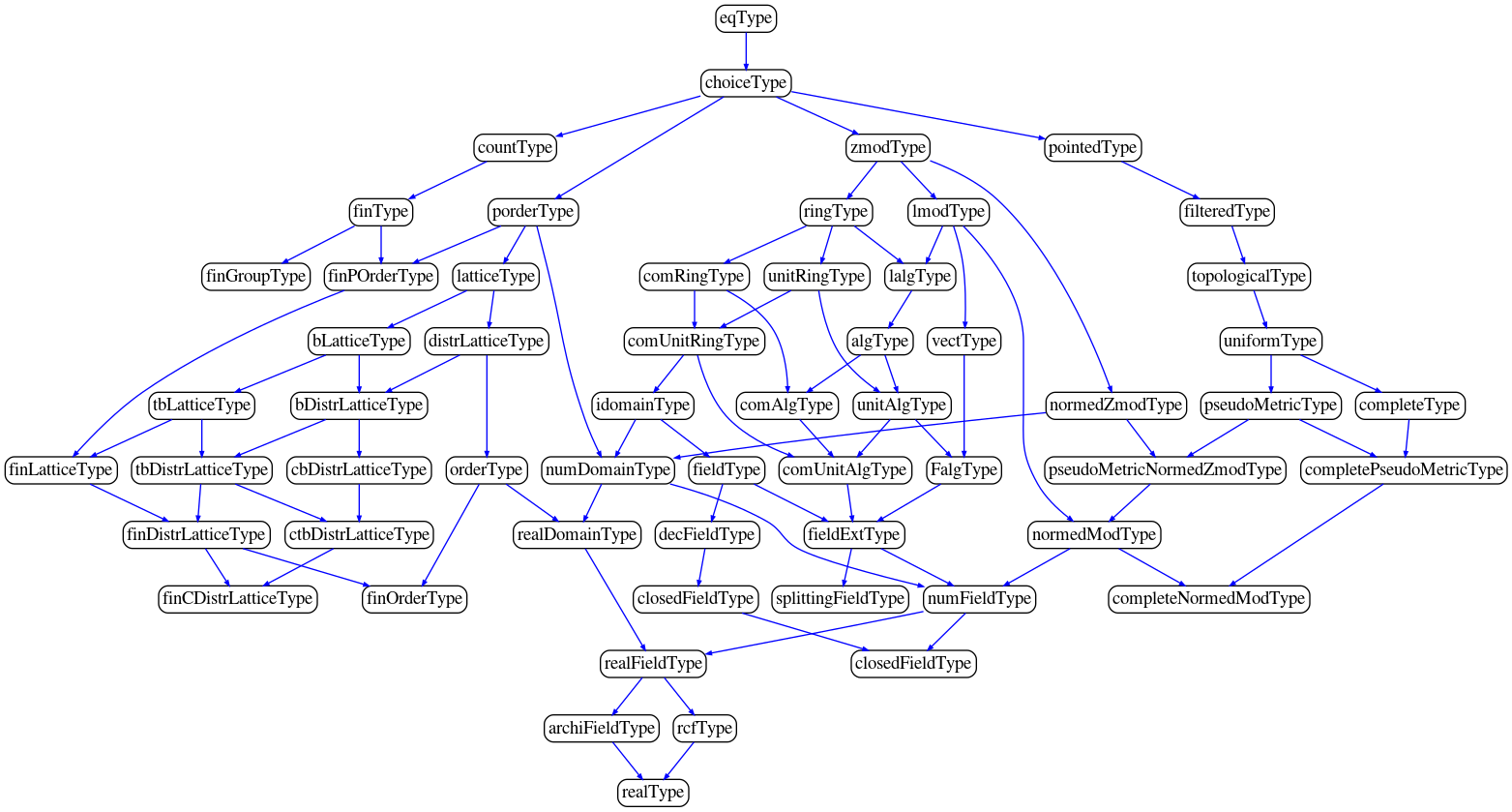

Programming and mathematics have much in common, philosophically. The disciplines deal with constructions of various kinds. The constructions can get arbitrarily complex and interconnected. As a result, it’s no surprise that concepts such as overloaded notations, implicit coercions and inheritance pop up frequently in both disciplines. For instance, a field inherits the properties of a ring, which in turn inherit from Abelian groups. The symbol + can mean different things depending on if we’re talking about vector spaces or coproducts. Mathematical structures even exhibit multiple inheritance. For instance, here’s the dependency graph of the real number type in the mathcomp-analysis library.

From left to right, the structures can be roughly classified as pertaining to order theory, algebra and topology. For the object-oriented programmer: how many instances of multiple inheritance do you see?

It’s important to capture the way structures are organized in mathematics in a proof assistant with some uniform strategy, well-known in the OOP world as “design patterns.” In this article I will catalogue and explain a selection of various patterns and their strengths and benefits. They are (in order of demonstration):

- typeclasses

- hierarchy builder

- packed classes and canonical structures

- structures and telescopes

- records

- modules

For convenience as a reference I will start with the most recommended elegant and boilerplate-free patterns to the ugliest and broken ones.

The running example will be a simple algebraic hierarchy: semigroup,

monoid, commutative monoid, group, Abelian group. That should be

elaborate enough to show how the approaches hold up in a more

realistic setting. Here’s an overview of the hierarchy we’ll be

building over a type A:

- Semigroup

add : A -> A -> A(a binary operation overA)addrA : forall x y z, add x (add y z) = add (add x y) z

- Monoid (inherits from Semigroup)

zero : Aadd0r : forall x, add zero x = xaddr0 : forall x, add x zero = x

- ComMonoid (inherits from Monoid)

addrC : addrC : forall (x y : A), add x y = add y x;

- Group (inherits from Monoid)

opp : A -> A(inverse function)addNr : forall x, add (opp x) x = zero(addition of an element with its inverse results in identity)

- AbGroup (inherits from ComMonoid and Group)

You may also see ssreflect style statements such as associative add.

Then, if all goes well, we will test the expressiveness of our hierarchy by proving a simple lemma, which makes use of a law from every structure.

(* Let A an instance of AbGroup, then the lemma holds *)

Lemma example A (a b : A) : add (add (opp b) (add b a)) (opp a) = zero.

Proof. by rewrite addrC (addrA (opp b)) addNr add0r addNr. Qed.

Typeclasses

Reading: Type Classes for Mathematics in Type Theory

A well-known and vanilla approach is to use typeclasses. This goes

very well, our declaration for AbGroup is just the constraints,

similar to how it would be done in Haskell. However, pay special

attention to the definition of AbGroup, there’s a ! in front of

the ComMonoid constraint to expose the implicit arguments again, so

that it can implicitly inherit the monoid instance from G.

Require Import ssrfun ssreflect.

Class Semigroup (A : Type) (add : A -> A -> A) := { addrA : associative add }.

Class Monoid A `{M : Semigroup A} (zero : A) := {

add0r : forall x, zero + x = x;

addr0 : forall x, x + zero = x

}.

Class ComMonoid A `{M : Monoid A} := { addrC : commutative add }.

Class Group A `{M : Monoid A} (opp : A -> A) := {

addNr : forall x, add (opp x) x = zero

}.

Class AbGroup A `{G : Group A} `{CM : !ComMonoid A}.

The example lemma is easily proved, showing the power of typeclass resolution in unifying all the structures.

Lemma example A `{M : AbGroup A} (a b : A)

: add (add (opp b) (add b a)) (opp a) = zero.

Proof. by rewrite addrC (addrA (opp b)) addNr add0r addNr. Qed.

See the accompanying gist for the instantation of the structures over ℤ.

Hierarchy Builder

The Hierarchy Builder (HB) package is best described as a boilerplate generator, but in a good way! From a usability point of view, it is similar to typeclasses.

First we define semigroups. HB.mixin Record IsSemigroup A declares

that we are about to define a predicate IsSemigroup over a type A,

and the two entries in the record denote the binary operation and its

associativity, respectively. We also define an infix notation for

convenience.

From HB Require Import structures.

From Coq Require Import ssreflect.

(* Semigroup definition *)

HB.mixin Record IsSemigroup A := {

add : A -> A -> A;

addrA : forall x y z, add x (add y z) = add (add x y) z;

}.

HB.structure Definition Semigroup := { A of IsSemigroup A }.

(* Left associative by default *)

Infix "+" := add.

Next we define monoids. Similarly to semigroups we use the mixin

command, but now declare the inheritance by of IsSemigroup A. That

is, for a type to be a monoid, it must be a semigroup first.

(* Monoid definition, inheriting from Semigroup *)

HB.mixin Record IsMonoid A of IsSemigroup A := {

zero : A;

add0r : forall x, add zero x = x;

addr0 : forall x, add x zero = x;

}.

HB.structure Definition Monoid := { A of IsMonoid A }.

Notation "0" := zero.

Now that we’ve seen two examples, there’s no surprises left on how to define commutative monoids and groups.

(* Commutative monoid definition, inheriting from Monoid *)

HB.mixin Record IsComMonoid A of Monoid A := {

addrC : forall (x y : A), x + y = y + x;

}.

HB.structure Definition ComMonoid := { A of IsComMonoid A }.

(* Group definition, inheriting from Monoid *)

HB.mixin Record IsGroup A of Monoid A := {

opp : A -> A;

addNr : forall x, opp x + x = 0;

}.

HB.structure Definition Group := { A of IsGroup A }.

Notation "- x" := (opp x).

Now for the interesting part. Hierarchy Builder makes it easy for us to do multiple inheritance and combine the constraints, much like typeclasses. Then we can seemlessly prove the lemma exactly as we did before.

(* Abelian group definition, inheriting from Group and ComMonoid *)

HB.structure Definition AbGroup := { A of IsGroup A & IsComMonoid A }.

(* Lemma that holds for Abelian groups *)

Lemma example (G : AbGroup.type) (a b : G) : -b + (b + a) + -a = 0.

Proof. by rewrite addrC (addrA (opp b)) addNr add0r addNr. Qed.

The underlying code it generates follows a pattern known as packed

classes (elaborated in the next section). For future-proofing, the

generated code can be shown by prefixing a HB command with

#[log]. When the HB.structure command is invoked, a bunch of

mixins and definitions are created. For brevity I’m omitted some of

them here.

...

Top_AbGroup__to__Top_Semigroup is defined

Top_AbGroup__to__Top_Monoid is defined

Top_AbGroup__to__Top_Group is defined

Top_AbGroup__to__Top_ComMonoid is defined

join_Top_AbGroup_between_Top_ComMonoid_and_Top_Group is defined

...

In more detail, here is the output of Print

Top_AbGroup__to__Top_ComMonoid., which shows that it is a coercion

that lets us go from an Abelian group structure to a commutative

monoid structure (i.e. going back up the hierarchy.) Hierarchy

Builder automatically creates these coercions and joins for us.

Top_AbGroup__to__Top_ComMonoid =

fun s : AbGroup.type =>

{| ComMonoid.sort := s; ComMonoid.class := AbGroup.class s |}

: AbGroup.type -> ComMonoid.type

Top_AbGroup__to__Top_ComMonoid is a coercion

It is worth noting that the math-comp library is undergoing a transition to use Hierarchy Builder in the future, instead of hand-written instances and coercions.

Packed classes & canonical structures

Reading: Canonical structures for the working Coq user

In the math-comp library, the approach taken is known as the packed classes design pattern. It’s a fairly complicated construct that I might elaborate more in a future blog post, but I’ll give some highlights and a full example.

Note that math-comp is being ported to Hierarchy builder, so this style is being phased out.

Telescopes

According to the Mathematical Components book,

Telescopes suffice for most simple — tree-like and shallow — hierarchies, so new users do not necessarily need expertise with the more sophisticated packed class organization covered in the next section

Here’s how to define a monoid. We create a module, postulate a type

T and an identity element zero of type T, and combine the laws

into a record called law. The exports section is small here but we

export just the operator coercion.

Module Monoid.

Section Definitions.

Variables (T : Type) (zero : T).

Structure law := Law {

operator : T -> T -> T;

_ : associative operator;

_ : left_id zero operator;

_ : right_id zero operator

}.

Local Coercion operator : law >-> Funclass.

End Definitions.

Module Import Exports.

Coercion operator : law >-> Funclass.

End Exports.

End Monoid.

Export Monoid.Exports.

With that defined, we can instantiate the monoid structure for

booleans (note that zero is automatically unified with true).

Import Monoid.

Lemma andbA : associative andb. Proof. by case. Qed.

Lemma andTb : left_id true andb. Proof. by case. Qed.

Lemma andbT : right_id true andb. Proof. by case. Qed.

Canonical andb_monoid := Law andbA andTb andbT.

Records

Let’s define a semigroup using one of the most basic features of Coq, records. Writing it this way means it is simply just a conjunction of laws as an n-ary predicate over n components. We define the semigroup structure first, then consider monoids as an augmented semigroup.

Require Import ssrfun.

Record Semigroup {A : Type} : Type := makeSemigroup {

s_add : A -> A -> A;

s_addrA : associative s_add;

}.

Record Monoid {A : Type} : Type := makeMonoid {

m_semi : @Semigroup A;

m_zero : A;

m_add0r : forall x, (s_add m_semi) m_zero x = x;

m_addr0 : forall x, (s_add m_semi) x m_zero = x;

}.

Unfortunately we already have to make an awkward choice to do some sort of indexing to access the underlying shared associative binary operation. At the next level when one defines groups as an augmented monoid, the situation only gets worse:

Record Group {A : Type} : Type := makeGroup {

m_monoid : @Monoid A;

g_inv : A -> A;

g_addNr : forall x, (s_add (m_semi m_monoid)) (g_inv x) x = m_zero m_monoid;

}.

We have to access the operation through two different indexes for

it! Perhaps we might want to add a member to the record that is equal

to the inherited operation, but this too is not satisfactory since it

prevents us from creating a canonical name for the operation in

question (for instance, add), and we’d have to do this at

arbitrarily nested levels. Thus, while flexible, this approach does

not scale.

Modules

One approach, seen in CPDT is to use the module system to organize the hierarchy. It seems fine for the first few structures. We declare parameterized modules and postulate additional axioms upon the structure from which it is inheriting from.

Require Import ssrfun.

Module Type SEMIGROUP.

Parameter A: Type.

Parameter Inline add: A -> A -> A.

Axiom addrA : associative add.

End SEMIGROUP.

Module Type MONOID.

Include SEMIGROUP.

Parameter zero : A.

Axiom add0r : left_id zero add.

End MONOID.

Module Type COM_MONOID.

Include MONOID.

Axiom addrC : commutative add.

End COM_MONOID.

Module Type GROUP.

Include MONOID.

Parameter opp : A -> A.

Axiom addNr : forall x, add (opp x) x = zero.

End GROUP.

However, we immediately run into an issue when trying to create a

Abelian group from a commutative monoid and group, this is because the

carrier type A is already in scope from the first include, so we

cannot share the carrier type (or even the underlying monoid) with

GROUP. So we give up.

Module Type COM_GROUP.

Include COM_MONOID.

Fail Include GROUP.

End COM_GROUP.

The command has indeed failed with message:

The label A is already declared.

Final thoughts

Just like software engineering, there are many ways to organize mathematical theories in proof assistants such as Coq.

Personally, I would lean more towards organizing my theories with Hierarchy Builder—or at the very least, typeclasses, if external dependencies are an issue.